Busting the Myth of the "Ideal" Workflow

What is the ideal IHC workflow? Should you run your slides in batches or process them in a continuous flow? Because your lab is unique, and each day is full of surprises, there may not be one ideal IHC workflow. This lecture will focus on how to identify gaps in your IHC workflow using data the lab currently collects and understanding how it correlates to items flowing though the laboratory. The key instead is to have an adaptable workflow that matches your lab’s daily needs. In this presentation, we will look at the importance of understanding what you are doing now, what tools you might use to analyze your process, and how to best decide on the right solutions for you.

Learning Objectives

- Identify critical points to your existing workflow using data you currently collect.

- Select tools to help you measure and improve the critical points identified.

- Understand the factors that help determine your optimal IHC workflow.

Webinar Transcription

Webinar Transcript

Welcome. My name is Ashley Troutman. I'm a senior marketing manager with Leica Biosystems. I wear a few different hats with the company and being an experienced workflow consultant is one of them. I've done almost 100 assessments over the years and the one thing I've learned is that I don't have all the answers, but I do have some good suggestions. I must share some of those with you today. Thank you for joining me.

The hot topic of workflow is on everyone's mind as we try to navigate some uniquely challenging times. As we continue to figure out how to shift our thinking and do things better, hopefully this quick workshop can introduce you to some high-level tools and concepts to look at your laboratory and your workflow to make some positive changes. Side note that these concepts and tools are valid throughout the histology lab and not just in IHC.

There are three primary outcomes you should have after we finish here. You should be able to identify some critical points to your workflow using data you probably already collect. You should have a high level of understanding of some common tools that should help you identify and improve the critical points in your current workflow. And finally, you should be able to recognize and understand some of the factors that can help you determine your optimal IHC workflow.

What do I mean by workflow? The Oxford Dictionary defines it as the sequence of industrial, administrative, or other processes which a piece of work passes from initiation to completion. Or for a slightly less wordy version, all the steps it takes to get from raw materials to finish product. What is important to remember is that workflow does not equal instrument. Although an instrument can influence your workflow, it should not necessarily dictate it.

Let's talk a bit about batch versus continuous processing. Each has its pros and cons. The advantages of batch processing are that it generally works well in high-volume, high-reagent usage situations and also with flexible turnaround times. Slides can also be easier to load depending on how you batch the slides. Additionally, reagent management is also less complicated because you do not have to load several vials of the same antibody. A disadvantage to batch processing includes the copious amounts of slide sorting that may be required before and after staining, depending on how you batch your slides.

On the flip side, an advantage to continuous processing is that it can be a more efficient process with less sorting due to keeping cases together throughout the process. Some of the disadvantages can be idle time when work is not coming in. This is mostly seen with cutoff times. I can already see the heads nodding. What I mean by this is the cutoff times translate to when you need to order, which can often result in most orders arriving within a two-minute window of the deadline. Therefore, the hours preceding the cutoff time can be predictably idle with a huge dump of orders happening all at once, closer to the order cut off time. This often happens during what we call high traffic hours. The time you were more apt to run out of space on your instruments because you had space earlier, but no slides to put on. Additionally, there can be a trade-off with less slide sorting, but more effort with reagent management and possibly reagent availability with continuous processing.

One of the first things to consider when looking at your IHC workflow is to understand that it does not exist in a vacuum. Don't look at the IHC lab in isolation. Tissue processing, embedding, sectioning, staffing, couriers, how the orders come in, and even the lab hours all contribute to the quality and workflow of IHC. What are your volumes? What is your basic process? You will also need to know your equipment and staffing constraints. How can you accommodate your volume with your staff and equipment? It is important to understand all these factors as they relate to your workflow the way that it is now.

Understanding how IHC fits into your overall process, it is important to understand all the areas that your IHC lab touches. Do you directly deal with the histology lab? Who handles the slides after they leave the IHC area? Are there couriers involved? Do you have a separate case assembly area? This is where you can start to see if there are stakeholders downstream that might be affected by any changes you make.

Let's now look a little deeper with the information you likely already have. First, consider your orders. How do you know what stains to run? How do you get those requests? Fax? Phone call? a paper form? Do you pull the information out of your LIS? Does the LIS send it directly to your instruments? I've been in labs that literally did all these methods at the same time. The techs were running around to five different places to make sure they had all the IHC orders. The take-home message here is that you preferably want one way to get your orders. The more ways you perform a process, the more opportunities for error.

Next, ask how and when do the specimens come in? Do you rely on external or internal couriers? Are you a reference lab or a specialty lab? Do your specimens come in via carrier like FedEx? Do you receive cut slides or paraffin blocks? Who cuts them? Are controls ready when the slides are? If you're processing previously cut unstained slides, how do they get to the lab? Hint: for IHC you need slides.

You might not receive slides, so you have to find out the best way to get them from what you receive, be it paraffin blocks or wet tissue to unstained slides. How you receive your work dictates your workflow.

Next, look at the amount of work you do. What is your average daily volume? Sometimes it's helpful to know the average number of slides per case or average slides per specimen. This can help you down the road if you're anticipating some level of expansion and all you know is the number of cases or specimens you will get. Of course, you will need to be sure to track what percentage of total cases get IHC testing to use that metric. While you are figuring out your average daily volume, look up the max number of slides you ran in a single day in, say, the last year. You might even get nostalgic and remember what a madhouse that day was. What is the absolute max number of slides you can physically do? You can perform a quick capacity analysis by figuring out the maximum slide throughput you can achieve within the working hours of the lab. That is often done in slides per hour or slides per day.

Next, you can look at some of your processes with time and motion studies, which may require some data collection if you do not have this information already. If you are cutting blocks, find out how long it takes to section a block. Be forewarned though, this will take a lot of examples. Cutting an IHC block can involve a lot of steps. If you cut your control along with your patient tissue, for example. Most IHC blocks do not require the same number of slides to be cut. To have the most useful data, you will need a lot of blocks over several days or weeks and performed by multiple operators. Do you have paperwork to manage? How long does it take to do that? What kind of daily maintenance do you have to perform? How much automation do you have? Do you bake your slides on your stainer or in a slide oven first? You perform antigen retrieval manually? Each of these parts of your process are important to document.

Finally, how many staff members do you have? Do you have lab assistants or just techs? How many hours do you dedicate staff to the IHC lab? Do you have multiple shifts, half shifts, or overlapping shifts?

Now that you have some baseline information about what you currently do, step back and change your perspective to where you want to be. Try to think about your lab the way an outsider might. Ask yourself what problem you are trying to solve. Do you want faster turnaround time? Are you anticipating increased volumes? Look at your data. If you need to take some measurements, now's the time to write down which ones. Consider things like the time and motion studies I mentioned earlier. A note about data, there's data, and then there's useful data. Many labs that I visit collect data just to collect data. Most of the time they collect it because someone higher up told them that they needed to. Please hear me on this, if you are collecting data and no one is using it to make decisions about your operation, you are wasting your time. Create a plan for your data and use accordingly.

Examples of useful data are volumes, staffing and work hours. Average turnaround time of an IHC run. All of those are necessary to be able to give you solid information to justify staffing hours and equipment.

Let's take a minute to talk about waste. Depending on whose textbook you read or what website you visit, there can be different considerations for lean waste. I want to speak specifically to these eight, since they're the most common in histopathology labs. The first is overproduction. This is defined as producing more than is necessary, leading to increased inventory. What does this mean for an IHC lab? Well, one example might be making up more diluted antibody or reagent than what is needed. This waste leads to the excess antibody losing its effectiveness over time or having to discard the excess antibody because it has expired.

The next waste is one we are probably all familiar with, wait time. This is simply, if you must wait for your work to show up. An example is when the lab must wait for slides from couriers stuck in traffic or work from other departments such as histology, cytology, hematology, and molecular.

Another example is when there is wait time because you cannot process work due to capacity staffing shortage or other reasons. Transportation waste is defined as unnecessary movement of product. An example of transportation waste is carrying slides to and from one counter to another and back again. This waste can often be remedied by relocation or rearrangement of equipment or furnishings.

Overprocessing is doing more work than is necessary. The best example is cutting extra unstained slides. Now if you use these, this probably is a good use of your time and wouldn't be considered over processing. However, I've seen and managed a lab they use less than 2% of these slides annually. I'm talking about tens of thousands of unstained slides each year that were stored and ultimately discarded. If you want to know how that story ended, I will tell you that the data I collected on this directly led to a change in how many unstained slides we cut going forward, and it was a dramatic difference and a huge cost savings.

Inventory is something usually discussed in manufacturing setting where you want to maintain a balance of production and having enough product on hand. You can apply this to your supply inventory and not filling your valuable space with storing items long term. You can manage inventory with items such as Kanban cards or electronic inventory control systems.

Motion waste refers to unnecessary movement by people. Transportation is product, motion is people. The best example of this is at a grossing station. You want to keep all the tools you use frequently right in front of you. Things like blades, ink, and gauze. You don't want to keep those on the top shelf all the time and must repeatedly reach for them.

Defects are anything that requires rework. Repeat staining or reprocessing a tissue block, especially when realizing this need during cutting would qualify as a defect. Finally, talent waste is underutilizing staff skills, talent or knowledge. Keep these in mind as you go through your own process and see if you can spot any. This is a potential win-win situation to get to improve the lab while improving job satisfaction, career track visibility, and other things.

As we look at the improvement phase, we will spend a few minutes looking at some of the tools used to examine data and help you make decisions about your workflow from the information you glean from it. The first tool is harder than it sounds using the five why's to determine root cause is very helpful if you do it correctly. It isn't just asking why five times, but each question must lead to the next like in this example.

Why are we not meeting our turnaround time? Because not all slides are getting stained. Why aren't all slides getting stained? Because we don't have enough space on the instruments. Why do we not have enough space on the instruments? Because all the orders come in at the same time. Why are all the orders coming in at the same time? Because we have cutoff times. Why do we have cutoff times? To ensure slide delivery by the end of the day, etcetera.

You might even notice this one turns into a circular problem. We aren't meeting our goal of getting the slides out on time because we are trying to ensure we get the slides out on time. This issue is a little more complicated than I intended to make it, but this is a great example of something you might routinely encounter when employing this technique. So how do we address it and solve it? Well, this issue along with many you will find, requires discussion with all the parties involved so that everyone understands what the issues are.

As mentioned, to correctly use the five why's, each subsequent question needs to follow the same line of questioning to dig deeper until you get an answer. Just remember, if the last answer to your root cause analysis is, “because that's how we've always done it,” you either need to start over or find a different answer.

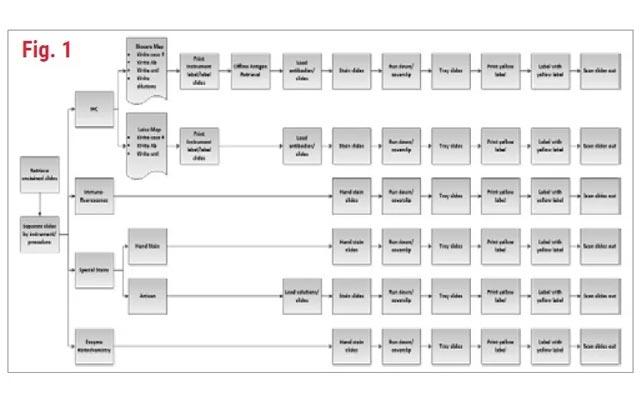

The next tool in our bag should be one of the easiest, but also one that you should take your time with. Process mapping is one of the best ways to visualize a process and pick up on little things you may not consciously be aware are happening. When you observe the process in action, do it several times and record everything, no matter how trivial. You might be surprised at some of the things you find out.

Pareto charts are a great way to look at a bunch of processes and issues and prioritize them based on how often they occur. In this example, I've taken the IHC processes in the lab and timed each step. When you graph it, and Excel has this function built in, it organizes them from longest time to shortest time. In this example minutes are on the left. Percentage for each item, the scale on the right side, shows the percentage or how long each task takes as part of the entire process. This is why when adding each item together, it adds up to 100%.

Spaghetti diagrams can be useful when you are evaluating transportation waste. Transportation waste is spent is time spent walking, say, from one side of the room to the other 10 or 20 times a day. This can easily identify opportunities to move some things around or otherwise optimize the step and flow of materials or slides in this case. In the before example on the left, you can see numerous lines moving back and forth between workstations. On the right is the modified workflow that reduces overall foot traffic and unnecessary movement.

The next tool we'll discuss is the impact matrix. An impact matrix is extremely useful for when you have a list of improvements or initiatives discovered so far to help determine which ones you could or should possibly work on. Using the Matrix Board, you can rank improvement opportunities, typically by how easy or difficult the initiative is to implement, and by how much impact this improvement would have on the overall process.

This is a great exercise for everyone to get in the same room and discuss each initiative and get an idea of how they compare to each other. There should be a lot of discussion around all these items because they will likely affect more than just the IHC lab. Include your pathologist and some representatives of the histology lab. What you may consider high value and low effort. Maybe high effort and low value for someone else. It is important to realistically gauge the overall impact and effort for the entire operation.

Generally, if it is difficult and low impact, it's best to avoid doing this initiative because the effort is not worth it from a payoff perspective. However, if it's easy to implement and has high impact, it's a no brainer and a win-win.

The last tool we will discuss are the tools you create yourself for the analysis of your lab. I'm pretty sure at least a few of you listening to this have some experience with spreadsheet programs. This tool is an example of something I created to catch your IHC work availability. By filling in the spreadsheet mostly with the number of slides and slide completion times, you can get the spreadsheet to graphically display clusters of when your IHC slides are completed each day.

This example assumes a continuous processing model which can give seemingly random end times throughout the day. However, if you get enough data points, you can start to see where they cluster, and those areas can help you schedule your employees to meet the work demand when you know most of the work is going to be available.

Let's talk about what to do with all this information. The analysis part of working with data is often the hardest part. The first thing is to understand what tools you need to use along the same line. What are the tools telling you? Keep in mind that some things will show up on your list that you cannot change right now, but you'll never make an effective change if you don't have a clear understanding of everything it takes to do the work.

Don't be disheartened if you have a lot of long-term items on your list. Sometimes you even must dive deeper into some of the bigger items to get something actionable. I've even seen some items go through three or four passes before a decision is made to act on something. You just need to get to the critical few.

Getting to the critical few can take some digging, but it is important so that you don't end up spinning your wheels on something that takes a ton of effort but has little value. Most of you probably realize that more isn't always better. More might help, but it might only be a temporary fix. Your data will tell the story. Once you get the data sorted out and the analysis done, don't be afraid to shoot for the moon. Use your data to defend your points, but anticipate resistance and be ready with solutions.

What is an adaptable workflow? It's a process that allows flexibility without compromising standard work. It can also be the ability to seamlessly integrate additional processes into your existing workflow. Standard work is the established procedure of how you do something. Being adaptable in the IHC lab may involve having a dedicated instrument for cytology specimens or rush specimens that follow the same procedures but don't necessarily fit with the rest of the workflow. Ultimately, being adaptable is thinking ahead and having a plan for things that will throw a monkey wrench into your day-to-day work.

We're going to walk through a quick example of using several of these tools to create your best workflow. First, we'll look at this basic process map. It has a simple IHC process with a single staining platform. This is a high-level process map for demonstration purposes and easy interpretation. Your process map should be considerably more detailed than this.

This slide is a little busy, but what I did was take some process measurements and put them in a spreadsheet. I have the average time for each step listed in the process map in minutes. After graphing the data, the Pareto chart lists each task from longest time to shortest time. This allows me to quickly see where I might find the low hanging fruit. I removed the actual staining step from the graph for two reasons. First, the staining portion of the process is going to be the least likely thing to change and second, it is the longest step and will make the graph difficult to read. Since this is a simple example, it's easy to see what the next longest process is. However, when you have numerous steps, the Pareto helps identify them easily.

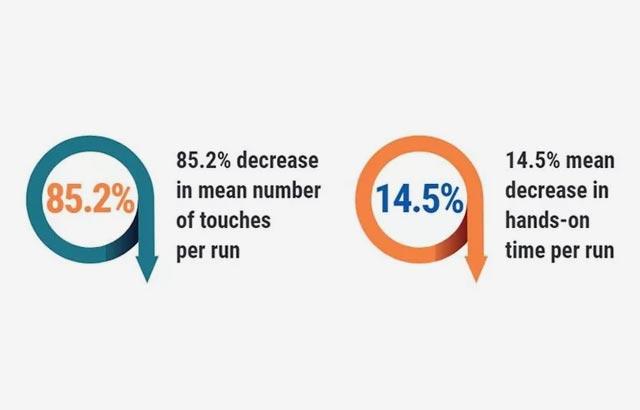

For this example, we see that the top three most time-consuming steps in the process are offline antigen retrieval, baking slides in the oven, and offline counter staining. Obviously, we can't eliminate any of these steps, but it may be worth exploring if automation will make a significant difference.

When undertaking a workflow project, it's worth reflecting on the project from a 10,000 foot perspective. From high up, when looking at your individual scenario, you may fall into one of the following three categories of workflow changes. The first is the blank slate. This is where there's no existing lab, no staff, no nothing. There's an idea, usually someone said we need to build a lab of what is needed, and you need to figure out the details.

Volume estimates are extremely important and having the wrong information can be disastrous. Make sure you list all your constraints, including your budget. You will need to know where your resources should be best spent, or at least have some data-driven reasons why. Again, when setting these up, they are not a one size fits all. Your lab’s goals drive the decisions to create the workflow that is right for the situation.

The next one is the remodel. This is the most common and the most diverse. This can range from shoehorning a new piece of equipment in to moving a lot of the furniture around. Usually we see this from when an increase in volume is expected or some new technology or equipment needs to find a home, or even when the lab hours have changed.

The last one is utopia. This is a large-scale overhaul that can accompany a merger or acquisition, an expansion, or the introduction of a significant new technology, such as a new lab information system, specimen tracking, or digital pathology. A technique that works well for me in many situations involves creating a perfect world workflow and then working backwards to figure out what parts of that perfect world you can keep and which ones you must work around.

To recap, identify your critical points with data. Start with some obvious things such as your turnaround time metrics, your volumes, staffing and even the things you already know that need fixing. Make a list. Consider trying some of the tools provided like process maps, Pareto charts, spaghetti diagrams and impact matrices. Or even create your own tool that specifically helps you track or measure something unique to your lab.

Finally, use analytical techniques to help you identify areas of your process that can be modified or eliminated to get you to your goals. Be cognizant of making changes to your process and how they affect all the associated processes. While you're fixing one thing you don't want to unintentionally break three more.

Some parting advice, if you go through all of this and don't have any ideas at the end of it, you've likely done something wrong. There's always something to examine, no matter how trivial it may seem. Also, finding a bunch of things to improve that cause you to look at it and say, “there's just no way we can do any of this,” is probably a good thing. This means that you need to start thinking about how you collect data to make your case, and getting those things changed.

To assist you with your workflow analysis, we'll be providing you with a workflow optimization toolkit featuring the tools presented. I hope this was helpful and reinforced what I think most of you already knew that there's no ideal workflow for a lab. Each lab has a unique set of goals and the means to achieve those goals. That's not to say we can't learn from each other and use some of the established practices and techniques. Work towards your labs goals and improving what you do for your patients. Thank you. I appreciate your time and I look forward to your questions.

About the presenter

Ashley Troutman has been involved in Laboratory Medicine for more than 20 years in clinical, research and administrative capacities. He has worked in facilities of all sizes, from small community hospitals and private labs to large academic medical centers and corporate reference labs. He has extensive experience in laboratory science and management, specifically in anatomic pathology and immunohistochemistry. He has managed routine histology operations and has been part of the team to aid researchers in designing experiments using histologic techniques. These roles have allowed Ashley to lead work process implementation teams that saw success in scientific innovation as well as improving laboratory efficiency through areas of waste/cost reduction, process improvement and safety.

Related Content

Die Inhalte des Knowledge Pathway von Leica Biosystems unterliegen den Nutzungsbedingungen der Website von Leica Biosystems, die hier eingesehen werden können: Rechtlicher Hinweis. Der Inhalt, einschließlich der Webinare, Schulungspräsentationen und ähnlicher Materialien, soll allgemeine Informationen zu bestimmten Themen liefern, die für medizinische Fachkräfte von Interesse sind. Er soll explizit nicht der medizinischen, behördlichen oder rechtlichen Beratung dienen und kann diese auch nicht ersetzen. Die Ansichten und Meinungen, die in Inhalten Dritter zum Ausdruck gebracht werden, spiegeln die persönlichen Auffassungen der Sprecher/Autoren wider und decken sich nicht notwendigerweise mit denen von Leica Biosystems, seinen Mitarbeitern oder Vertretern. Jegliche in den Inhalten enthaltene Links, die auf Quellen oder Inhalte Dritter verweisen, werden lediglich aus Gründen Ihrer Annehmlichkeit zur Verfügung gestellt.

Vor dem Gebrauch sollten die Produktinformationen, Beilagen und Bedienungsanleitungen der jeweiligen Medikamente und Geräte konsultiert werden.

Copyright © 2026 Leica Biosystems division of Leica Microsystems, Inc. and its Leica Biosystems affiliates. All rights reserved. LEICA and the Leica Logo are registered trademarks of Leica Microsystems IR GmbH.